|

|

Ibero-American Journal of Psychology and Public Policy eISSN 2810-6598 |

Research Article DOI: 10.56754/2810-6598.2025.0021 |

Procedural and distributive justice and life satisfaction in teenage students

Justicia procedimental y distributiva y satisfacción con la vida en estudiantes adolescentes

Martha Frías-Armenta1,* and Beatriz Valenzuela-García2

1 Law

Department, Universidad de Sonora, Mexico; martha.frias@unison.mx ![]()

2 Education

Department, Universidad de Sonora, Mexico; beatriz.valenzuelag04@gmail.com

![]()

* Correspondence: martha.frias@unison.mx; phone number: +526622592170

|

Reference: Frías-Armenta, M., & Valenzuela-García, B. (2025). Procedural and distributive justice and life satisfaction in teenage students (Justicia procedimental y distributiva y satisfacción con la vida en estudiantes adolescentes). Ibero-American Journal of Psychology and Public Policy, 2(1), 81-114. https://doi.org/10.56754/2810-6598.2025.0021 Editor: Carolina Hausmann-Stabile Reception date: 03 May 2024 Acceptance date: 24 Sept 2024 Publication date: 28 Jan 2025 Language: English and Spanish Translation: Helen Lowry Publisher’s Note: IJP&PP remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Copyright: © 2025 by the

authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms

and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY NC SA) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses |

Abstract: Previous studies have shown evidence of a relationship between distributive and procedural justice and adolescent and child life satisfaction. This highlights the need to increase knowledge and create instruments to assess these constructs, particularly in the Latin American context. Thus, the study aimed (1) to explore the psychometric properties of procedural justice (PJ) and distributive justice (DJ) instruments in a sample of northwest Mexican students and (2) to assess the relationship between PJ, DJ, and life satisfaction (LS). The sample included 208 students (Mage = 13.5; SD = 0.92). Univariate statistics, Cronbach's alpha, McDonald's omega, and Spearman's rho correlation coefficients were calculated. Further, confirmatory factor analyses were tested for each construct, a covariance model and a structural equation model were tested. Instruments assessing PJ and DJ showed acceptable internal consistency and convergent and discriminant validity. The relationship between the factors indicated that the greater the perception of justice in school life, the better the students’ reported life satisfaction. Keywords: equity in the process; well-being; adolescence; fairness in allocation; validity; reliability. Resumen: Estudios previos han revelado una relación entre la justicia distributiva y procedimental y la satisfacción con la vida de estudiantes adolescentes. Esta asociación hace necesaria la generación de conocimiento y la creación de escalas para medir estos constructos en el contexto latinoamericano. Por lo tanto, el objetivo de este estudio fue explorar las propiedades psicométricas de las escalas de justicia procedimental (JP) y justicia distributiva (JD) y la relación de estos dos constructos con la satisfacción con la vida (SV) en adolescentes. La muestra incluyó a 208 estudiantes (Medad = 13.5; DE =0.92). Se calcularon estadísticas univariadas, el alfa de Cronbach, el omega de McDonald y el coeficiente de correlación rho de Spearman entre las escalas. Igualmente se probaron análisis factoriales confirmatorios para cada constructo, un modelo de covarianza y un modelo de ecuaciones estructurales. Todas las escalas mostraron consistencia interna, y validez convergente y discriminante. La relación entre los factores indicó que entre más fuerte es la percepción de justicia escolar de los estudiantes, mejor es su satisfacción con la vida. Palabras clave: equidad en el proceso; bienestar; adolescencia; equidad en la asignación; validez; confiabilidad. Resumo: Estudos anteriores mostraram evidências de uma relação entre justiça distributiva e processual e adolescentes e satisfação com a vida infantil. Isso destaca a necessidade de aumentar o conhecimento e criar instrumentos para avaliar esses construtos, especialmente no contexto latino-americano. Assim, os objetivos do estudo foram (1) explorar as propriedades psicométricas dos instrumentos de justiça processual (JP) e justiça distributiva (JD) em uma amostra de estudantes do noroeste mexicano e (2) avaliar a relação entre PJ, DJ e satisfação com a vida (SV). A amostra foi composta por 208 estudantes (Midade = 13,5; DP = 0,92). Estatísticas univariadas, Alfas de Cronbach, Ômegas de McDonald e Spearman Além disso, análises fatoriais confirmatórias foram testadas para cada construto e um modelo de covariância, e um modelo de equações estruturais foram testados. Os instrumentos que avaliaram PJ e DJ apresentaram consistência interna, e validade convergente e discriminante. A relação entre os fatores indicou que, com uma percepção de maior justiça na vida escolar, os estudantes relataram maior satisfação com a vida. Palavras-chave: justiça no processo; bem-estar; adolescência; equidade na alocação; validade; confiabilidade.

|

1. Introduction

Justice represents an important avenue of study in the context of education. Mesias et al. (2022) indicate that just pedagogies support well-being in schools. There is recent interest in promoting well-being in schools and investigating its relationship to just conditions or opportunities that allow the development of all students (Ramírez‐Casas del valle et al., 2021). In addition, justice in schools is associated with student life satisfaction (Elovainio et al., 2011). Korpershoek (2020) found that students’ perceptions of teachers’ fairness influenced the sense of student school belonging. Moreover, the meta-analysis by Wong et al. (2022) reveals a relationship between school belonging and academic achievement, self-efficacy, and other variables. de la Cruz Flores (2022) proposes five axes for public policies based on equity in Mexico. The first is to repair the social order, establishing educational policies where students are treated fairly; the second advocates inclusion; the third challenge is related to defining policies about equity; the fourth refers to transformation of the school model; and the fifth is to promote the teachers training as agents of change, and all of them related to school justice.

Justice is seen as a value embedded in society (Singh, 2023) and can be broadly defined as the adoption of equal rights and fair procedures in the allocation of assets (Petersmann, 2003). More specifically, justice can be understood as the distribution of resources and obligations (Liebig & Sauer, 2016). These definitions reflect two frameworks for understanding justice (Martin et al., 2020): (1) one related to fairness in process (procedural justice); (2) another refers to the degree of equality in the distribution of assets, rights, and obligations (distributive justice). Procedural justice (PJ) has been defined as the perceived fairness of treatment from authorities (Prusiński, 2020) or the perceived fairness of processes and rules (Tyler, 2006). Distributive justice (DJ) has been conceptualized as perceived fairness in the distribution of benefits and burdens (Jafino et al., 2021), as well as the perception of fairness in resource allocation (Moroni, 2020). Procedural and distributive justice models have been studied from the perspective of the general population and their compliance with authorities and the law (Bello & Matshaba, 2021; Pina-Sánchez & Brunton-Smith, 2020).

Learning environments focusing on fair and clear processes and procedures also train students in the basic elements of justice, which allow them to experience and internalize the principles of justice and peaceful conflict resolution. Justice in school focuses on students’ development of skills to modify or address situations of concern in support of their own rights (Henríquez, 2018). Justice in the school setting could be built with a culture of respect for students’ rights, care, and inclusion, enabling children and adolescents to develop healthy relationships and collaborative learning. In this sense, schools should be responsible for establishing clear rules, processes, and educational policies related to student behaviors (Goldblum et al., 2015).

Prilleltensky et al. (2023) argue that PJ and DJ are necessary for optimal human development. Empirical evidence has demonstrated a relationship between PJ, DJ, and life satisfaction (Lucas et al., 2016). Thus, the relationship between justice and well-being needs to be better understood. This understanding may improve student educational and developmental outcomes such as affirmation as valuable and loved people, the connection with the school, the formation of students in principles of equity, respect for human rights and social skills. However, more research is necessary.

1.1 Procedural justice

Procedural justice (PJ) refers to the perception of the process in assigning assets, benefits, or results (Ruano‐Chamorro et al., 2022). The influence of the treatment of authority while allocating resources or resolving conflicts was integrated into the concept (Chan et al., 2023; Jackson et al., 2015). Similarly, it is related to the perception of the fairness of the stages taken in the designation of the resources (Ryan & Bergin, 2022).

Specialists in the field consider that PJ principles are properly applied if the person is treated with dignity and respect throughout the process and is allowed to present their point of view (Nagin & Telep, 2020). In addition, PJ refers to impartiality in the process and if this process is based solely on facts and evidence without favoring any of the parties involved (Van Hall et al., 2024). This type of justice is also related to procedures based on clear and previously established rules applied consistently over time and seeks transparency in the process, explaining why and how a process determination was made (Jackson et al., 2015; Murray et al., 2021; Tyler, 2006).

Empirical evidence suggests PJ can improve school climate within the educational context. For instance, Brasof and Peterson (2018) researched the effectiveness of Youth Court programs in three high schools that promoted PJ when addressing school rule violations. Student volunteers directed cases requiring disciplinary action; sentences could include oral and written apologies to the victim, community service, peer mediation, and mentoring. Youth courts gave students a voice and control in the process. Students in this program perceived the process as fair, and it is thought this helped reduce problematic behavior.

Since secondary school students are minors and have the right to be represented by their parents or guardians in legal, civil, and administrative proceedings, transparency must also include their families (International Association of Youth and Family Judges and Magistrates [AIMJF], 2017). In such settings, transparency should apply primarily in admissions processes, student experience development (including school rules), and evaluations (Meijer, 2009). Liu and Hallinger (2024) found that a school climate with PJ moderated the effects of instructional leadership on teacher responsibility. Compliance with school rules can be improved when the actions of authorities are perceived to be just. Previous research suggests students are more likely to accept the decisions of school disciplinary authorities when they perceive their experience as fair and respectful (Woolard et al., 2008). Evidence also shows that school PJ enhances school performance (Dunning‐Lozano et al., 2020).

Procedural justice, specifically in schools, integrates processes that highlight individual differences in student upbringing and cultural exposure (Prilleltensky et al., 2023; Varela, 2020). In addition, to have PJ, the school community must communicate institutional regulations, evaluation criteria of their courses, as well as the mechanisms of communication to complain, protest, or negotiate in case of possible conflicts (Valente et al., 2020). In this sense, Carreto-Bernal and Rosales-Sánchez (2023) argue that PJ in school discipline could improve social relations and avoid social discrimination.

1.2 Distributive Justice

Distributive justice (DJ) refers to the perceived fairness in the actual distribution of objects or resources among potential recipients; these can be rights, income, freedoms, opportunities, outcomes, well-being, and even disciplinary measures (Green, 2022). Several principles of DJ guide the distribution of assets, where equity is one of the main tenets (Bolívar, 2012). Equity corresponds to the equivalence between the contributions or effort invested (merit) and the result; it is sensitive to the differences between people, such as supporting disadvantaged groups with greater resources (Bolívar, 2012). Henríquez (2018) mentions three additional principles: 1) equality, which refers to an equal distribution of any given good in all of those involved; 2) prioritization, which results in actions that benefit those who are afflicted with a greater lack of a good, increasing their level of well-being; and 3) sufficiency, whose objective is for people to reach a degree of well-being that would allow to possess all that is necessary to live adequate conditions. These elements have been studied in different settings in the school context and are related to the allocation of grades, recognition, rights, disciplinary measures, and obligations. The literature suggests that many current school systems do not have an equitable distribution of benefits and burdens (Lünich et al., 2024).

An investigation in the educational setting associated grade placement with the perception of DJ in high school adolescents from Israel and Germany (Resh & Sabbagh, 2017). They reported that a considerable proportion of students in both countries judged their grades as unfair (on average, 51% of Israeli students and 28% of German students), claiming they received lower grades than they deserved. Further, they also reported that, in both countries, males perceived a higher level of unfairness.

It is worth mentioning that the DJ principles are applicable in the school context, both in public policies and in daily dynamics. In the latter, instrumental rewards (e.g., grades, recognition, certificates) and social rewards (e.g., respect, concern for others, friendship) are constantly "distributed" among students. The fair or unfair allocation of rewards has been a relevant research topic for decades due to the potential impact on their academic career (Lünich et al., 2024). Likewise, the perception of fair treatment by teachers and other school community members fosters student commitment, promotes academic success, is directly related to the joy of learning, and promotes a positive environment (Donat et al., 2016).

1.3 Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction (LS) can be defined as a feeling of happiness and well-being (Sholihin, 2022) or as a subjective evaluation of the person’s achievement of their expectations and goals (Aymerich et al., 2021). Life satisfaction is the psychological component of well-being (Losada-Puente et al., 2020) and, specifically, one of the elements of subjective well-being. It is composed of three subfactors: a) global satisfaction with life, b) positive affective states, and c) relative absence of negative events (Ruggeri et al., 2020). Life satisfaction is a cognitive component of subjective well-being (Ahmadi & Ahmadi, 2020). It is defined as a person’s evaluation of their general well-being (Steptoe et al., 2015). Promoting LS can be a protective factor for adolescent students, as it is linked with various positive emotions and can protect them from the harmful effects of stressful life events (Cavioni et al., 2021).

Huebner (1994) studied the LS in children, evaluating it with the Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (MSLSS). This instrument covers domains regarding the presence and significance of their relationships, such as family, friends, themselves, school, and their environment. Gilligan and Huebner (2007) adapted the scale for adolescents (MSLSS-A), maintaining the five domains and including items on relationships with people of a different gender.

Recent studies have found that the school and family contexts have also been associated with life satisfaction in secondary students (Povedano-Diaz et al., 2020) and, more specifically, justice in school has also been linked to better academic performance and improved student well-being (Elovainio et al., 2011). However, few studies have explored PJ, DJ, and LS in the secondary school setting. Nelson et al. (2014) tested the relationship between perceived PJ in teaching practices, conflict management styles, and attitudes towards adolescent students. They found that students who perceived that their teachers acted fairly and paid attention to them showed less inclination to challenge them when they disagreed with their decisions. Likewise, their level of collaboration increased, either by accepting their decisions or showing a willingness to reach agreements (Ahmed et al. 2021). Resh and Sabbagh (2017) found evidence that, in general, students who perceived their teachers as fair tended to refrain from violent and dishonest acts and to participate in extracurricular activities and community volunteer service. In general, a sensitive school climate, including equitable strategies, enhances the quality of life for school children (Stilwell et al., 2024). Moreover, Mendoza Cazarez (2022) indicates that the experience of justice in the school environment helps achieve the two purposes of education: agency and well-being.

The association between justice and life satisfaction has also been studied in cultures around the world. Lucas et al. (2016) analyzed several types of justice and their relationship to promoting well-being in university students in various cultures. They shaped the construct of “justice beliefs” based on people’s perceptions and their own and others’ experiences of PJ and DJ. They assessed these beliefs in 922 university students in the United States, Canada, India, and China. In all four cultures, belief in DJ for oneself was associated with greater LS, whereas belief in PJ for oneself was associated with LS only for Canada and China. Castillo and Fernández (2017) conducted a study to assess the relationship between organizational justice (interactional, procedural, and distributive) and LS of 621 university students. They found that DJ and interactional justice were predictors of LS; however, PJ was unrelated to LS. The authors argued that this result might be due to PJ being measured generally, questioning students about their perception of institutional processes without considering the direct relationship between students and teachers. Sense of fairness indirectly affected LS in secondary school students in Iran (Ahmadi & Ahmadi, 2020). These findings suggest that DJ and PJ are associated with life satisfaction in the school context in various countries.

Despite these clear links and the fact that adolescence is one of the stages of greatest learning in human beings, where the principles of justice take shape in the actions of everyday life, there is a significant paucity of research exploring how PJ and DJ are perceived in schools. Similarly, aspects of justice are extremely relevant in forming adolescents as future citizens; few studies and instruments make it possible to assess their perception in the school environment despite being one of the most influential (and problematic) aspects at this stage of development. There is also little research evidencing the impact of the perception of DJ and PJ in schools on students’ life satisfaction, even though experiencing justice in all contexts of life is essential for its realization (Prilleltensky et al., 2023). Generally, the perception of PJ and DJ research in adolescents and, therefore, the valid and reliable tools created to assess it are relevant in the legal context and specifically for studies involving juvenile offenders (López Escobar & Frías Armenta, 2014;) or adolescents in high-risk environments (Fagan & Tyler, 2005). Despite their great relevance and important social impact, these topics have not been studied in the school context during adolescence.

Given the previous literature and relevance, the present study aims to contribute to the knowledge of secondary school students’ perception of PJ and DJ, constituting one of the first studies conducted in Mexico. It also aims to generate valid and reliable tools to study these constructs, which are essential to promoting school harmony (Secretaría de Educación Pública, 2018). Finally, it explores the relationship between the perception of justice in students and self-reported LS.

2. Objectives

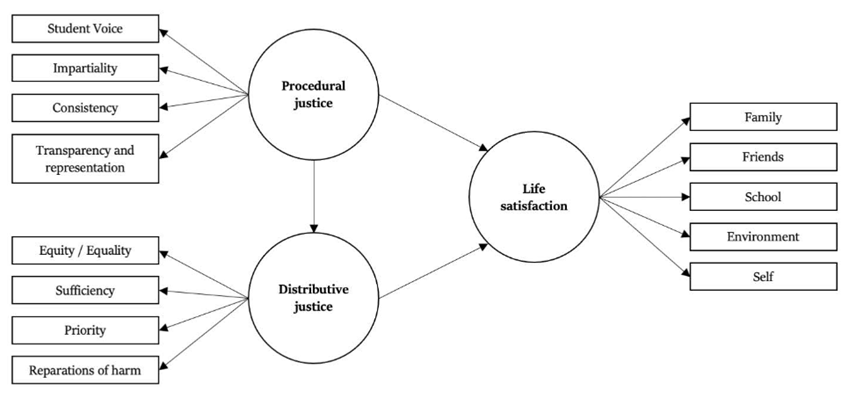

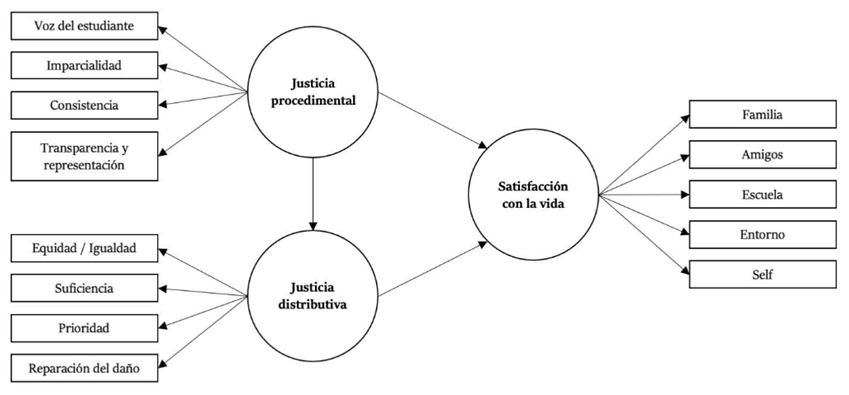

The main goal of the study was to investigate the relationship between life satisfaction and PJ and DJ in adolescents in the school context. Two objectives are derived: (1) Explore the psychometric properties of the MLSS-A, PJ, and DJ scales in a sample of secondary school students in a city in northwestern Mexico, and (2) Investigate the relationship between PJ, DJ, and the LS of adolescents in a school context. The hypothesized relationships are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Theoretical model between procedural justice, distributive justice, and life satisfaction

3. Method

3.1 Participants

The sample consisted of 208 students from two secondary schools (all three levels) in a city in northwestern Mexico, where 98 reported being male (47.1%) and 110 female (52.9%). Participants were between 12 and 16 years old (Mage = 13.5; SD =0.92). Of the total sample, 64.4% (134 students) attended a publicly funded school, and the remaining 35.6% (74 adolescents) studied in a privately funded school. Regarding their schooling level, 31.7% (66 students) were in first grade, 46.2% in second grade (96), and 22.1% in third grade (46).

3.2 Design

This correlational research aims to describe the relationship between the proposed variables (Hernández-Sampieri & Mendoza, 2023). It is considered prospective and cross-sectional since the information was collected expressly for the study, measuring the variables of interest on a single occasion (Hernández-Sampieri & Mendoza, 2023).

3.3 Instruments

3.3.1 Procedural Justice Scale

The Procedural Justice Scale (PJS; see Appendix A) is an instrument adapted from the Procedural Justice Scale by Frías-Armenta et al. (2016), which showed evidence of construct validity and reliability (α = 0.86). It consists of 21 Likert-type items (e.g., When you disagree with your grades and request a review, how fair do you think the teachers’ grading clarification process is?) with a 10-point scale (from 0 = not at all, unfair, never to 10 = all, fair, always). The instrument integrates the International Association of Youth and Family Judges and Magistrates criteria (AIMJF, 2017), which Jackson et al. (2015), Meijer (2009), and Tyler (2006) state must be present for a process to be considered fair. It includes six items on consistency, 7 on impartiality, 4 on transparency and representation, and 4 on the student’s voice. The instrument assessed the perception of fairness experienced during their entrance and throughout their stay in secondary school. Special focus was given to the admission process, class evaluation process, and how school regulations are implemented.

3.3.2 Distributive Justice Scale

The Distributive Justice Scale (DJS; see Appendix B) consists of 18 Likert-type items (e.g., I believe that asking for clarification on how I’ve been graded has helped me, as I get a fair grade) that use a 10-point scale (from 0 = completely disagree, not at all, never to 10 = completely agree, at all, always). Based on principles from Bolívar (2012) and Henríquez (2018), the DJS is considered indispensable in the study of DJ. Items assessed equity/equality (6 items), reparation of harm (4), sufficiency (4), and prioritization (4). The instrument evaluated the perception of the fair distribution of benefits received during their time in a secondary school associated with the admission process, the evaluation of classes, and the implementation of school regulations as a day-to-day procedure and when being disciplined. Frías-Armenta et al. (2016) showed evidence of construct validity and reliability (α = 0.93).

3.3.3 Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale

The Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (MSLSS-A; Gilligan & Huebner, 2007) is an instrument translated into Spanish and validated by San Martín (2011; see Appendix C). The MSLSS-A consists of 40 items in a 5-point Likert-type (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) that evaluates the LS of the adolescents based on their responses in 5 domains or areas: family (7 items), friends (9), school (8), living environment (9), and self-satisfaction (7). San Martín (2011) reported adequate levels of internal consistency for the scale in a Chilean sample (α = 0.89 for the complete instrument and between 0.79 and 0.90 for the domains). Although the scale may have some limitations, it offers an ecological perspective, including characteristics of central significance for adolescents (Losada-Puente et al., 2020). The scale has been previously adapted to Arabic and demonstrated validity and reliability (Veronese & Pepe, 2020). It was also validated in Spain and Chile, showing acceptable internal consistency and reliability (α = 0.86 in Spain) and (α = 0.88 in Chile) and construct validity.

3.3.4 Sociodemographic questionnaire

The sociodemographic variables were 12 open-ended items designed to collect information about the student's characteristics, such as age, gender, public or private schooling, parental education level, and if the student had paid employment. Information about monthly family income was also requested, where the student was asked to self-report by selecting one of 6 ranges, they considered applicable to their family situation.

3.4 Procedure and ethical considerations

First, school principals were informed of the objective of the project and what would be required of the students if they decided to participate. They were presented with the instruments so they could revise the content. Authorization from the parents or guardians was requested after the research procedures and objectives were explained to them. Informed consent forms were handed to students to be read and signed by their parents or guardians.

Students were told what the study consisted of and what their role would be if they decided to participate. The conditions of their collaboration (anonymous, voluntary, and with no effect on grading) were communicated to them. One day after consent forms were sent to parents, the forms were collected from the students. Only those students whose parents gave their consent to participate were given a second form, which was a student consent form. If students agreed to participate in accordance with the ethical standards for research work in psychology (Sociedad Mexicana de Psicología, 2009), the previously described instruments were distributed. A pencil and paper format was used, and it took approximately 30 minutes to complete.

3.5 Analytic strategy

In the first phase, continuous and categorical variables of the study were analyzed, and means, standard deviations, and frequencies were calculated using the SPSS v23 statistics package (Field, 2020). Subsequently, the normality of the data was determined based on the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk indicators. Cronbach's alpha (α) and McDonald's omega (ω) coefficients were also calculated for each scale to estimate its internal consistency. An average score for each subscale (4 for the PJS, 4 for the DJS, and 5 for the MSLSS-A) was calculated (Malkewitz et al., 2023). Finally, the Spearman's Rho correlation coefficient was estimated to determine whether the relationships between the scales of each construct were significant.

In the second phase of data analysis, various analyses were performed using the EQS v6 statistics program (Bentler, 2006). The robust maximum likelihood (MLR) method of estimation was used since the data did not present a normal distribution (Mardia’s statistic = 52.73; p <.05). Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted to demonstrate the convergent validity of the items of the DJ and PJ subscales. Subsequently, the average variance extracted (AVE) of each factor was calculated. The AVE is the average of the square of the lambda coefficients, and its value must be greater than 0.50 to be considered acceptable. Then, a covariance model was assessed to estimate the discriminant validity using PJ, DJ, and LS as correlated factors. The square root of the AVE values had to be greater than the covariances between the factors to demonstrate discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2021).

Finally, a structural equation model was tested to evaluate the direct and indirect effects of PJ and DJ on LS (Sürücü & Maslakçı, 2020; Urbina, 2014). To measure the relevance of the two models (covariance and structural models), we considered their goodness-of-fit indicators, which indicate whether the data supported the relationships specified in the hypothesized model. Since the significance of the chi-square statistical indicator (χ2) is sensitive to sample size, the relative χ2 was considered (χ2/df), expecting a value of less than 5 (Urbina, 2014). The practical indicators estimated were the Bentler-Bonett normed fit index (BBNFI), the Bentler-Bonett nonnormed fit index (BBNNFI), and the comparative fit index (CFI), which should produce a value greater than 0.90 (Hair et al., 2021). To measure the reasonable approximation error concerning the goodness of fit, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was used, which requires a value < .08 (Collier, 2020). In addition, a mediation model using the PROCESS macro for SPSS was performed, where the independent variable was PJ, the dependent variable was satisfaction with life, and the mediating variable was DJ.

4. Results

4.1 Internal consistency

The Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald's omega (ω) of all the scales and subscales showed internal consistency between the indicators of each construct. Table 1 shows internal consistency for each of the scales.

Table 1

Internal consistency of the scales and subscales

|

Scales and subscales |

α |

ω |

|

Procedural Justice |

.90 |

.90 |

|

Student Voice |

.78 |

.80 |

|

Impartiality |

.77 |

.78 |

|

Consistency |

.67 |

.68 |

|

.69 |

.70 |

|

|

Distributive Justice |

.92 |

.92 |

|

Equity/Equality |

.82 |

.83 |

|

Sufficiency |

.81 |

.81 |

|

Prioritization |

.75 |

.76 |

|

Reparations of harm |

.71 |

.71 |

|

Life Satisfaction |

.90 |

.90 |

|

Family |

.85 |

.84 |

|

Friends |

.78 |

.78 |

|

School |

.79 |

.79 |

|

Environment |

.78 |

.78 |

|

Self |

.85 |

.85 |

Note. α = Cronbach’s alpha; ω = McDonald’s omega

4.2 Convergent validity

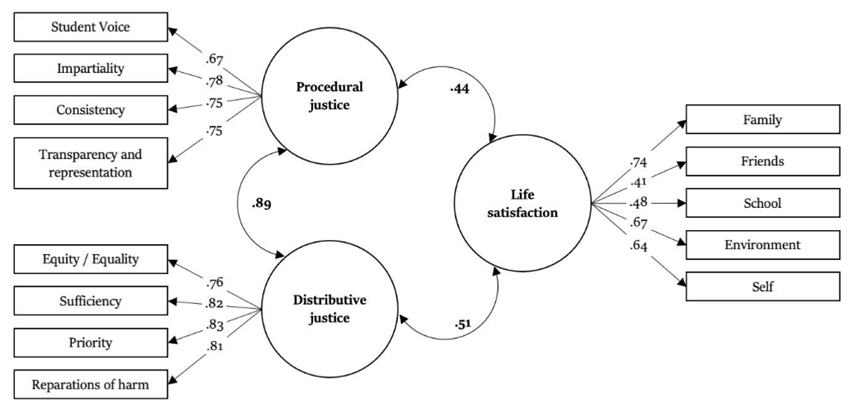

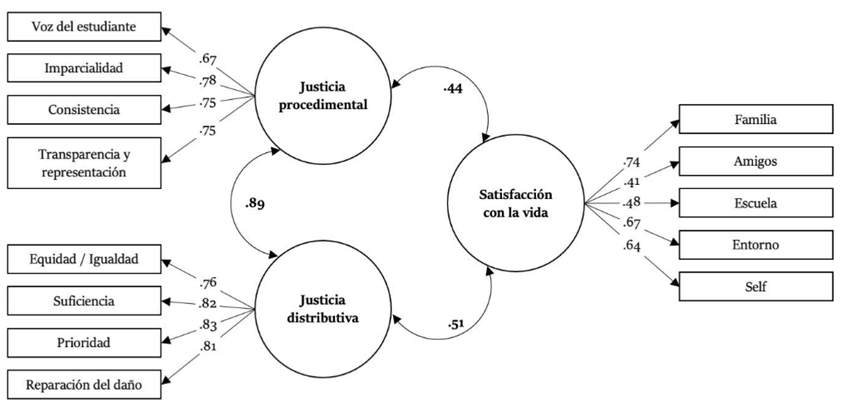

Confirmatory factor analyses evidenced acceptable statistical and practical goodness of fit, suggesting that the theoretical proposals fit the data well (see Table 2). It is worth mentioning that three items were eliminated on the MSLSS-A scale (one for the school domain and two for the living environment domain) because they decreased the inter-item correlation. AVE values were also acceptable (AVEPJ = .55; AVEDJ = .65), supporting the convergent validity of the items.

4.3 Discriminant validity

A covariance model with the three constructs was used to calculate the discriminant validity between PJ and life satisfaction, and DJ and life satisfaction. Significant correlations between PJ and DJ (ϕ = .89, p < .o5), PJ and LS (ϕ = .44, p < .05), and DJ and LS (ϕ = .51, p < .05) were found. The statistical and practical goodness-of-fit indices showed that the theoretical model fits the data well, χ2(62) = 89.29, p = .013; χ2/df = 1.44; BBNFI = 0.924; BBNNFI = 0.969; CFI = .975, and RMSEA = .046. The covariances between life satisfaction and PJ, and life satisfaction and DJ were smaller than the relationships between the constructs and their indicators. The square root of the AVE in PJ (0.74) and in DJ (0.81) were higher than the bivariate correlation of each subscale with LS, demonstrating adequate discriminant validity of the two types of justice compared to life satisfaction.

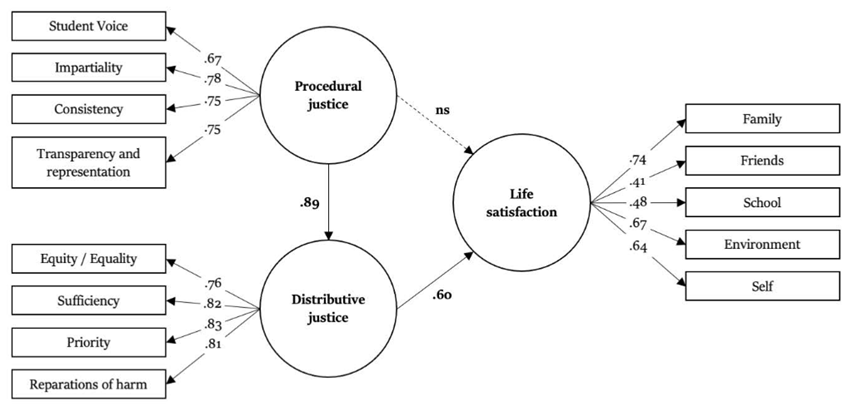

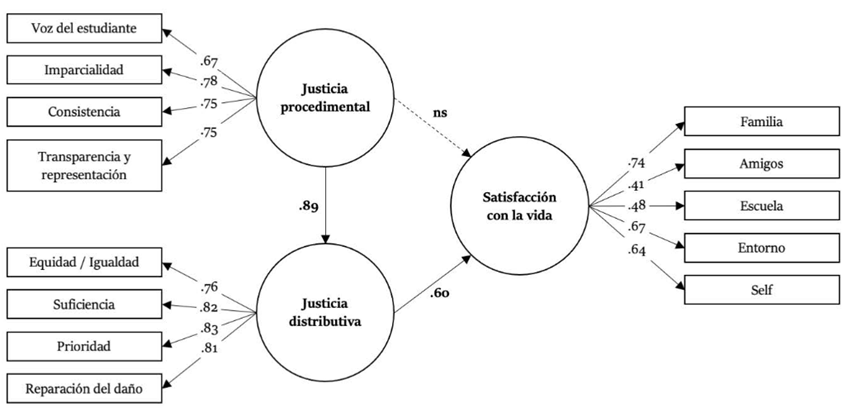

4.4 Mediational model

Using the covariance

model as a reference, a second model was calculated to test the direct (PJ on

LS and PJ on DJ) and indirect (PJ on LS through DJ) effects (see Figure 3). The goodness-of-fit indices were the same since the latent

variables were the same. Results showed that PJ directly and positively affects

DJ (γ = 0.89, p <.05); similarly, DJ directly and positively

affects LS (β = 0.60, p < .05).

However, the direct effect of PJ on LS was non-significant (γ = .10, p

>.05). There was an indirect effect of PJ on LS through DJ. The model

explains 27% of the variance of LS (R2 = .268).

Table 2

Goodness-of-fit indices from the confirmatory factor analyses

|

Chi-square test of model fit |

||||||||

|

Constructs |

χ2 |

df |

p |

χ2/df |

BBNFI |

BBNNFI |

CFI |

RMSEA |

|

Student Voice |

0.10 |

1 |

0.74 |

0.10 |

1.00 |

1.02 |

1.00 |

0.00 |

|

Impartiality |

24.56 |

13 |

0.02 |

1.88 |

0.90 |

0.92 |

0.95 |

0.06 |

|

Consistency |

12.94 |

9 |

0.16 |

1.43 |

0.92 |

0.95 |

0.97 |

0.04 |

|

Transparency and representation |

1.29 |

2 |

0.52 |

0.64 |

0.98 |

1.02 |

1.00 |

0.00 |

|

0.98 |

2 |

0.61 |

0.49 |

0.99 |

0.01 |

1.00 |

0.00 |

|

|

Reparations of harm |

0.42 |

2 |

0.80 |

0.21 |

0.99 |

1.04 |

1.00 |

0.00 |

|

Prioritization |

2.07 |

2 |

0.35 |

1.03 |

0.98 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.01 |

|

Equity/Equality |

17.82 |

9 |

0.03 |

1.98 |

0.93 |

0.94 |

0.96 |

0.06 |

|

Family |

9.62 |

13 |

0.72 |

0.74 |

0.96 |

1.01 |

1.00 |

0.00 |

|

Friends |

52.5 |

25 |

0.00 |

2.1 |

0.88 |

0.90 |

0.93 |

0.07 |

|

School |

9.44 |

12 |

0.66 |

0.78 |

0.97 |

1.01 |

1.00 |

0.00 |

|

Environment |

28.56 |

12 |

0.66 |

2.38 |

0.97 |

1.01 |

1.00 |

0.00 |

|

Self |

49.23 |

14 |

0.00 |

3.51 |

0.92 |

0.91 |

0.94 |

0.11 |

Figure 2

Confirmatory factor analysis of procedural justice, distributive justice, and life satisfaction

Structural equation model of the relationship between procedural justice, distributive justice, and life satisfaction

Note. ns = non-significant effect

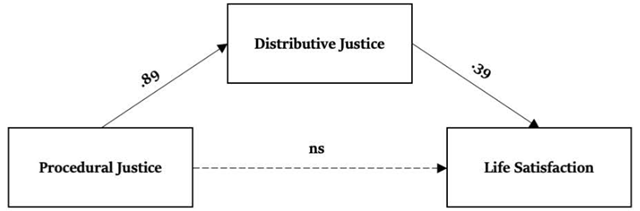

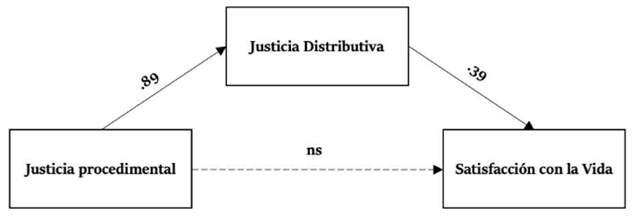

Due to the limitations of the EQS software in reporting the mediation effect, Model 4 of Hayes (2012) was calculated to obtain the indirect impact of PJ on life satisfaction. Procedural justice had an effect on DJ (B = 0.86, SE = .04, 95% CI [0.77, 0.94], β = 0.81, p < .001), and in turn, DJ had an effect on life satisfaction (B = 0.12, SE = .03, 95% CI [0.05, 0.18]; β = 0.39, p < .001). The model accounted for approximately 21% of the variance. The indirect effect was tested using a bootstrap percentile with an estimation approximation of 5,000 samples implemented using the PROCESS macro version 4.2 in SPSS. The results indicated that the indirect coefficient was significant (B = 0.13, SE = .02, 95% CI [0.09, 0.17] and partially standardized β = 0.39). Procedural justice associated with life satisfaction was .13 times higher when mediated by DJ since PJ was not a significant predictor of life satisfaction after controlling for the mediating variable (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Path analysis of the relationship between procedural justice, distributive justice, and life satisfaction

Note. ns = non-significant effect

5. Discussion

The present study provided evidence of validity and reliability for the Procedural and Distributive Justice Scales and tested the effect of two types of justice on life satisfaction in a sample of adolescents in Mexico. The results showed evidence that the inferences derived from the instruments (PJ, DJ, and LS scales) are reliable (Field, 2020) and valid (Hair et al., 2021; Urbina, 2014; Sürücü & Maslakçı, 2020). The items showed the relevance of the theoretically proposed criteria (AIMJF, 2017; Bolívar, 2012; Henríquez, 2018; Jackson et al., 2015; Meijer, 2009 & Tyler, 2006). Results also provided evidence of the feasibility of studying justice in the educational context. Additionally, it can broaden our understanding and promote the students’ holistic development, including training in building positive social relationships (Del Rey et al., 2017). Education should provide the school community with appropriate mechanisms for students to exert their rights so they can be respected (Woolard et al., 2008).

Our results also show that the Spanish translation of the MSLSS-A scale (San Martín, 2011) has evidence of reliability and validity in a Mexican sample. Our data showed the original factor structure, where life satisfaction had the same domains: family, friends, self, school, and the environment where the adolescent lives. Unlike previous studies, the school and living environment dimensions consisted of seven items each; three were eliminated, one for school and two for environment (Urbina, 2014). These items might have caused a reduction in internal consistency because they were reverse-coded (e.g., I feel bad at school), which could cause confusion while answering the instrument (DeVellis, 2016). The square root of AVE values compared to the PJ-LS and DJ-LS covariances suggested discriminant validity between the two types of justice (procedural and distributive) and the life satisfaction scale (Hair et al., 2021). However, the covariance between PJ and DJ was greater than the relationship between the indicators in each factor (Urbina, 2014), suggesting that these measurements of justice share theoretical aspects. This may be because people tend to shape their perception of justice considering three interrelated aspects: whether the experience has favorable or unfavorable results for them, whether the outcome is equitable (both elements of DJ), and whether the decisions were the product of fair processes (Tyler, 2019). When the two types of justice were assessed, our participants tended to respond to both instruments, considering their perception of general school justice as if it were a single unified construct (Resh & Sabbagh, 2017).

The structural model showed evidence of concurrent validity (Urbina, 2014). Significant relationships between the constructs studied made meeting the second study objective possible. Our results suggest that the students' perceived DJ is positively related to their self-reported LS. Contrary to our hypothesis, we found no significant effect of PJ on LS. However, we did find an association between PJ and DJ in the first model of 3-correlated factors. The structural model provided a significant indirect path through which PJ can influence the LS in adolescents via DJ. These findings suggest that the more aspects of their school life they perceive as impartial and equitable, with the opportunity to express their opinion or perceive school disciplinary measures as fair, the greater the satisfaction that adolescents experience in their lives. This is consistent with Henríquez (2018) reports of harmonious and balanced order, where each person receives what is due and benefits from the repair of the harm they may have suffered.

Previous research has reported a null relationship between PJ and LS, finding only the influence of DJ on LS (Castillo & Fernández, 2017). The present study shows evidence that DJ is a mediating variable between PJ and LS, i.e., students will perceive justice in school processes if they are able to identify it in the results obtained during their academic career. The evidence also suggests that this, in turn, can contribute to their perception of LS. Similarly, the present results confirm previous findings, where the greater the perception of school justice, the higher the level of involvement of students in extracurricular projects and community aid, activities that can also lead to better academic life satisfaction (Resh & Sabbagh, 2017). Likewise, our results are consistent with previous literature demonstrating a decrease in LS, specifically in the school domain, as a result of perceived student unfair treatment, like not allowing them to share their point of view on issues that involved them or deliberately ignoring it, or unjustified and excessive disciplinary measures (Brasof & Peterson, 2018).

In agreement with previous studies (Meijer, 2009) and various international organizations (AIMJF, 2017), this study provides evidence of the importance of integrating aspects of transparency and representation of procedural justice in adolescents' schools. The literature suggests inadequate management of PJ and DJ principles in education, particularly concerning the enforcement of the regulations that govern community school actions, underscoring the urgent need to train both administrators and educators on aspects that lead to improvement of the application of the principles of justice (Landeros & Chávez, 2015). Our research and previous studies (Bolívar, 2012; Henríquez, 2018) have highlighted that it is equally important to consider DJ given the impact this may have on their motivation, academic self-perception, school career, and future professional development (Resh & Sabbagh, 2017). Thus, it is essential to review continually and, if necessary, rethink the institutional criteria for grades, certifications, recognitions, or other types of student assessments.

These results could help promote the foundations that de la Cruz Flores (2022) recommends for equity-based public policies. The axes promoted by this author consist of establishing educational policies where students are treated fairly, so promoting programs with PJ and DJ policies in schools could help student well-being. Similarly, DJ and PJ support equity, impartiality, and prioritization of marginalized groups, which can lead to teaching students to practice justice and equity in the school context. Additionally, the principles of PJ and DJ are engines of transformation, not only in school life but in society in general. Once students learn them in school, they will externalize them to their family life and, in general, to society.

Carreto-Bernal and Rosales-Sánchez (2023) also argue for promoting PJ in school public policies. They suggest that this may confer transparency on the admission processes, which would lead to compliance with the right to education. Therefore, public policies in schools should include elements of PJ in its admission, evaluation, and school regulation processes, as well as in the support services and conflict resolution mechanisms. A special emphasis should be placed on promoting and offering dignified and fair treatment of students by teachers, authorities, and peers. This will allow the school administration to legitimize its authority and have students commit to complying with the established regulations (Tyler, 2006; Woolard et al., 2008).

Results from the present study need to be further replicated to assess generalizability and greater scope. Two main limitations of the current study that should be addressed in future studies are the use of self-reporting and non-probability sampling. Self-reporting as a source of information can lead to social desirability in the participants. In this sense, students may have responded by considering what would be appropriate for them to answer and not what they really perceive in a given situation. The student sample was non-probabilistic, potentially affecting the responses to our questionnaire. We worked with students who voluntarily agreed to participate. However, to have a more inclusive sample, we attempted to include students from public and private schools from the morning and afternoon sessions. Future studies should also include larger samples, which may allow for the study of other variables that are also important in the school context. This may facilitate the generalization and extension of our findings to a larger sector of the student population.

6. Conclusions

The results provide evidence that a student’s participation in the process and distribution of assets and obligations in the schools is related to greater life satisfaction. They are also particularly relevant given that this topic goes beyond the inferred educational sphere. During adolescence, individuals begin to form their understanding of equity, morality, and honesty. At this stage, students can cultivate critical skills of self-agency in their development as individuals (Le et al., 2024). Therefore, education policies should not only be oriented to the fair distribution of learning but also to the equitable participation of students in its distribution of assets and responsibilities as well as processes. Public policies to achieve fairer societies should include the participation of children and adolescents in educational processes (Mendoza Cazarez, 2022). Given the magnitude of this challenge, this study also provides evidence of the reliability and validity of the tools to evaluate the student’s perception of justice in one of the environments where they participate the most: their school. Given the importance of school justice in student life satisfaction, the results discussed in the present study can be considered in the formulation of public policies, curricular updates, modifications in teacher training programs, reconsideration of school rules, and other measures aimed at incorporating the principles of justice in schools, which for a long time have been ignored.

Justicia procedimental y distributiva y satisfacción con la vida en estudiantes adolescentes

La justicia representa una importante aproximación al estudio de la educación. Mesias et al. (2022) indican que las pedagogías justas favorecen el bienestar de estudiantes en las escuelas. En la actualidad, se ha generado un creciente interés en fomentar el bienestar de estudiantes dentro de los entornos escolares, así como en investigar cómo este se relaciona con condiciones u oportunidades que favorezcan el desarrollo integral de todos los estudiantes (Ramírez‐Casas del valle et al., 2021). Además, la justicia en las escuelas está asociada con la satisfacción con la vida (SV) de los/las estudiantes (Elovainio et al., 2011). Korpershoek (2020) encontró que las percepciones de los/las estudiantes sobre la imparcialidad de los/las profesores influyeron en su sentido de pertenencia escolar. Adicionalmente, el metaanálisis de Wong et al. (2022) ha identificado una correlación entre la pertenencia escolar y el logro académico, la autoeficacia, entre otras variables. de la Cruz Flores (2022) propone cinco ejes para las políticas públicas basadas en la equidad en México. El primero es reparar el orden social, estableciendo políticas educativas donde los/las estudiantes sean tratados con justicia, el segundo aboga por la inclusión, el tercer reto está relacionado con definir políticas sobre equidad, el cuarto se refiere a la transformación del modelo de escuela, y el quinto es promover la formación del profesorado como agentes de cambio, y todos ellos están relacionados con la justicia escolar.

La justicia se considera un valor arraigado en la sociedad (Singh, 2023) y puede definirse en términos generales como la adopción de la igualdad de derechos y procedimientos justos en la asignación de bienes (Petersmann, 2003). Más específicamente, la justicia puede entenderse como la distribución de recursos y obligaciones (Liebig & Sauer, 2016). Estas definiciones reflejan dos marcos para entender la justicia (Martin et al., 2020): (1) uno relacionado con la equidad en el proceso (justicia procedimental); (2) otro se refiere al grado de igualdad en la distribución de bienes, derechos y obligaciones (justicia distributiva). La justicia procedimental (JP) se ha definido como la equidad percibida en el trato por parte de las autoridades (Prusiński, 2020) o la equidad percibida en el proceso y las normas (Tyler, 2006). La justicia distributiva (JD) se ha conceptualizado como la equidad percibida en la distribución de beneficios y cargas (Jafino et al., 2021), así como la percepción de equidad en la asignación de recursos (Moroni, 2020). Los modelos de justicia procedimental y distributiva se han estudiado desde la perspectiva de la población en general y su conformidad con las autoridades y la ley (Bello & Matshaba, 2021; Pina-Sánchez & Brunton-Smith, 2020).

Los entornos de aprendizaje que se enfocan en procesos y procedimientos justos y claros también forman a los/las estudiantes en los elementos básicos de la justicia. Esto les facilita experimentar e interiorizar los principios de la justicia y la resolución no violenta de conflictos. La justicia en la escuela se centra en el desarrollo de habilidades de los/las estudiantes para modificar o abordar situaciones de preocupación en apoyo de sus propios derechos (Henríquez, 2018). La justicia en el contexto escolar podría construirse con una cultura de respeto a los derechos de los/las estudiantes, cuidado e inclusión, y ofrecer a los niños, niñas y adolescentes la oportunidad de desarrollar relaciones saludables y aprendizaje colaborativo. En este sentido, las escuelas deben ser responsables de establecer reglas, procesos y políticas educativas claras relacionadas con las conductas de los/las estudiantes (Goldblum et al., 2015).

Prilleltensky et al. (2023) sostienen que la JP y la JD son necesarias para un desarrollo humano óptimo. Las pruebas empíricas han demostrado una relación entre la PJ, la DJ y la SV (Lucas et al., 2016). Por consiguiente, resulta imperativo profundizar en la comprensión de la interacción entre la justicia y el bienestar. Esta comprensión puede mejorar los resultados educativos y de desarrollo de los/las estudiantes, así como su afirmación como personas valiosas y queridas, su conexión con la escuela, su formación en principios de equidad, el respeto de los derechos humanos y las habilidades sociales. Sin embargo, es necesario seguir investigando.

1.1 Justicia procedimental

La justicia procedimental (JP) se refiere a la percepción del proceso en la asignación de bienes, beneficios o resultados (Ruano-Chamorro et al., 2022). En el concepto se ha incorporado la influencia del trato de la autoridad durante el proceso de asignación de recursos o resolución de conflictos (Chan et al., 2023; Jackson et al., 2015). Asimismo, se vincula con la percepción de la equidad en las etapas de la asignación de los recursos (Ryan & Bergin, 2022).

Los expertos en la materia sostienen que los principios de JP se cumplen adecuadamente al tratar a la persona con dignidad y respeto a lo largo del proceso y se le permite exponer su punto de vista (Nagin & Telep, 2020). Además, la JP se refiere a la imparcialidad en el proceso, y si este proceso se basa únicamente en hechos y pruebas sin favorecer a ninguna de las partes implicadas (Van Hall et al., 2024). Este tipo de justicia también se relaciona con procedimientos basados en reglas claras y previamente establecidas, aplicadas de manera consistente en el tiempo, y busca la transparencia en el proceso, explicando la lógica y la metodología detrás de la determinación de proceso (Jackson et al., 2015; Murray et al., 2021; Tyler, 2006).

En el contexto educativo existen pruebas empíricas que sugieren que la JP puede mejorar el clima escolar. Por ejemplo, Brasof y Peterson (2018) investigaron la efectividad de los programas de Tribunales escolares de Menores en tres escuelas secundarias que promovieron la JP al abordar las infracciones de las reglas escolares. Los/las estudiantes voluntarios/as dirigieron los casos que requerían medidas disciplinarias; las sanciones podían incluir disculpas orales y escritas a la víctima, servicios a la comunidad, mediación por pares y tutoría. Estos tribunales escolares de menores dieron voz y control en el proceso a los/las estudiantes. Los/las que participaron en este programa percibieron el proceso como justo y se cree que esto ayudó a reducir el comportamiento problemático.

En el caso de los/las estudiantes de secundaria, la transparencia debe incluir también a sus familias, por ser menores de edad y tener derecho a ser representados por sus padres o tutores en procedimientos judiciales, civiles y administrativos (International Association of Youth and Family Judges and Magistrates [AIMJF], 2017). En estos contextos, la transparencia debería aplicarse principalmente en los procesos de admisión, en el desarrollo de la experiencia del/a estudiante (incluida la aplicación de las normas escolares) y en las evaluaciones (Meijer, 2009). Liu y Hallinger (2024) descubrieron que un clima escolar con JP moderaba los efectos del liderazgo instructivo sobre la responsabilidad de los/las profesores. El cumplimiento de las normas escolares se puede mejorar cuando las acciones de las autoridades se perciben como justas. Investigaciones anteriores sugieren que es más probable que los/las estudiantes acepten las decisiones de las autoridades disciplinarias escolares cuando perciben su experiencia como justa y respetuosa (Woolard et al., 2008). La evidencia también demuestra que la JP escolar mejora el rendimiento escolar (Dunning-Lozano et al., 2020).

La JP, específicamente en lo que se refiere a los contextos educativos, incorpora procesos que destacan las diferencias individuales en la crianza y exposición cultural de los/las estudiantes (Prilleltensky et al., 2023; Varela, 2020). Además, para que exista JP es fundamental que la comunidad escolar comunique los reglamentos institucionales, los criterios de evaluación de sus cursos, así como los mecanismos de comunicación para reclamar, protestar o negociar en caso de posibles conflictos (Valente et al., 2020). En este sentido, Carreto-Bernal y Rosales-Sánchez (2023) argumentan que la JP en la disciplina escolar podría potenciar las relaciones sociales y prevenir la discriminación social.

1.2 Justicia distributiva

La justicia distributiva (JD) se refiere a la equidad percibida en la distribución real de objetos o recursos entre los receptores potenciales; estos pueden ser derechos, ingresos, libertades, oportunidades, resultados, bienestar e incluso sanciones (Green, 2022). Varios principios de la JD guían la distribución de bienes, donde la equidad es uno de los principios fundamentales (Bolívar, 2012). La equidad corresponde a la equivalencia entre los aportes o esfuerzo invertido (mérito) y el resultado; es sensible a las diferencias entre las personas como apoyar con mayores recursos a los grupos desfavorecidos (Bolívar, 2012). Henríquez (2018) menciona tres principios adicionales: 1) igualdad, que se refiere a una distribución equitativa de un determinado bien entre todos los involucrados; 2) priorización, que se traduce en acciones que benefician a quienes padecen una mayor carencia de un bien, aumentando su nivel de bienestar; y 3) suficiencia, cuyo objetivo es que las personas alcancen un grado de bienestar que les permita poseer todo lo necesario para vivir en condiciones adecuadas. Estos elementos han sido estudiados en diferentes ámbitos en el contexto escolar y están relacionados con la asignación de calificaciones, el reconocimiento, los derechos, las sanciones y las obligaciones. La literatura sugiere que muchos sistemas escolares actuales no tienen una distribución equitativa de beneficios y cargas (Lünich et al., 2024).

Una investigación en el ámbito educativo asoció la asignación de calificaciones con la percepción de JD en adolescentes de secundaria de Israel y Alemania (Resh & Sabbagh, 2017). Esta encontró que una proporción significativa de estudiantes de ambos países juzgaban sus calificaciones como injustas (en promedio, el 51% de los/las estudiantes israelíes y el 28% de los alemanes), alegando que habían recibido calificaciones más bajas de las que merecían. Además, también reportaron que, en ambos países, los hombres percibían un mayor nivel de injusticia.

Cabe mencionar que los principios de JD se pueden aplicar en el contexto escolar, tanto en las políticas públicas como en las dinámicas cotidianas. En este último, las recompensas instrumentales (p. ej., calificaciones, reconocimiento, certificados) y las recompensas sociales (p. ej., respeto, preocupación por los demás, amistad) se «distribuyen» constantemente entre los/las estudiantes. La asignación justa o injusta de recompensas ha sido un tema de investigación relevante durante décadas debido al impacto potencial en su trayectoria académica (Lünich et al., 2024). Igualmente, la percepción de un trato justo por parte de los/las profesores y otros miembros de la comunidad escolar fomenta el compromiso de los/las estudiantes, promueve su éxito académico y está directamente vinculada con la alegría de aprender y el fomento de un entorno positivo (Donat et al., 2016).

1.3 Satisfacción con la vida

La satisfacción con la vida (SV) puede definirse como un sentimiento de felicidad y bienestar (Sholihin, 2022) o como una evaluación subjetiva del logro de las expectativas y metas de las personas (Aymerich et al., 2021). La SV es el componente psicológico del bienestar (Losada-Puente et al., 2020) y, en concreto, uno de los elementos del bienestar subjetivo. Se compone de tres subfactores: a) satisfacción global con la vida, b) estados afectivos positivos, y c) ausencia relativa de acontecimientos negativos (Ruggeri et al., 2020). La SV se considera un componente cognitivo del bienestar subjetivo (Ahmadi & Ahmadi, 2020). Se define como la evaluación que hacen las personas de su bienestar general (Steptoe et al., 2015). La promoción de la SV puede representar un factor de protección para los/las estudiantes adolescentes, dado que está relacionada con varias emociones positivas y puede protegerlos de los impactos perjudiciales de los sucesos estresantes de la vida (Cavioni, et al., 2021).

Huebner (1994) estudió la SV en niño/as, evaluándolo con la Escala Multidimensional de Satisfacción con la Vida de los/las Estudiantes (Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale - MSLSS). Este instrumento comprende áreas relacionadas con la presencia y relevancia de sus relaciones, tales como la familia, los amigos, ellos/ellas mismos/as, la escuela y el entorno en el que viven. Gilligan y Huebner (2007) adaptaron la escala para adolescentes (MSLSS-A), manteniendo los cinco dominios e incluyendo ítems sobre relaciones con personas de distinto género.

Estudios recientes han encontrado que el contexto escolar y familiar también se ha asociado a la SV en estudiantes de secundaria (Povedano-Díaz et al., 2020) y más específicamente la justicia en la escuela también se ha relacionado con un mejor rendimiento académico y un mayor bienestar del estudiantado (Elovainio et al., 2011). Sin embargo, pocos estudios se han desarrollado sobre JP, JD y SV en el contexto de la escuela secundaria. Nelson et al. (2014) comprobaron la relación entre la JP percibida en las prácticas docentes, los estilos de gestión de conflictos y las actitudes hacia los/las estudiantes adolescentes. Descubrieron que los/las estudiantes que percibían que sus profesores actuaban con justicia y les prestaban atención mostraban menos inclinación a desafiarles cuando no estaban de acuerdo con sus decisiones. Asimismo, incrementó su nivel de colaboración, ya fuera aceptando las decisiones de sus profesores o mostrando su disposición a llegar a acuerdos (Ahmed et al., 2021). Resh y Sabbagh (2017) encontraron evidencia de que, por lo general, los/las estudiantes que veían a sus profesores como justos se inclinaban a evitar conductas violentas y deshonestas, y a involucrarse en actividades extracurriculares y en el voluntariado en la comunidad. Un clima escolar sensible, que incluya estrategias equitativas, generalmente mejora la calidad de vida del estudiantado (Stilwell et al., 2024). Además, Mendoza Cazarez (2022) indica que la experiencia de justicia en el ambiente escolar ayudará a alcanzar los dos fines de la educación: agencia y bienestar.

La asociación entre justicia y SV también se ha estudiado en culturas de todo el mundo. Lucas et al. (2016) analizaron diversos tipos de justicia y su relación con la promoción del bienestar en estudiantes universitarios de diversas culturas. Dieron forma al constructo «creencias de justicia» basándose en las percepciones y experiencias de las personas tanto para sí mismas como para los demás del JP y el JD. Evaluaron estas creencias en 922 estudiantes universitarios de los Estados Unidos, Canadá, India y China. En las cuatro culturas, la creencia en el JD para uno mismo se asoció con una mayor SV, mientras que la creencia en el JP para uno mismo solo se asoció con SV en el caso de Canadá y China. Castillo y Fernández (2017) realizaron un estudio cuyo propósito fue evaluar la relación entre la justicia organizacional (interaccional, procedimental y distributiva) y la SV en 621 estudiantes universitarios. Descubrieron que la JD y la justicia interaccional eran predictores de la SV; sin embargo, la JP no estaba relacionada con la SV. Los autores sostuvieron que este resultado podría atribuirse a que JP realiza una medición global, interrogando a los estudiantes sobre su percepción de los procesos institucionales, sin considerar la relación directa entre estudiantes y profesores. El sentido de justicia tuvo un efecto indirecto sobre la SV en estudiantes de secundaria en Irán (Ahmadi & Ahmadi, 2020). Estos resultados sugieren que la JD y JP están asociadas con la SV en el contexto escolar en varios países.

A pesar de estas evidentes relaciones y de que la adolescencia es una de las fases de mayor aprendizaje en el ser humano, donde los principios de justicia se reflejan en las acciones diarias, hay una notable falta de estudios que investiguen la percepción de JP y JD en las escuelas. De igual manera, a pesar de que los elementos vinculados a la justicia son de gran relevancia en la formación de los adolescentes como futuros ciudadanos, hay escasos estudios e instrumentos que nos faciliten valorar su percepción en el entorno escolar, a pesar de ser uno de los factores más impactantes (y problemáticos) en esta fase de desarrollo. También son escasas las investigaciones que aportan evidencias sobre el impacto de la percepción de la JD y JP en la SV de los/las estudiantes en las escuelas, a pesar de que experimentar la justicia en todos los escenarios de la vida es esencial para su logro (Prilleltensky et al., 2023). En términos generales, la investigación de la percepción de JP y JD en adolescentes y, por tanto, los instrumentos válidos y fiables creados para evaluarla, son relevantes en el contexto jurídico y específicamente para estudios que involucran a menores infractores (López Escobar & Frías Armenta, 2014) o adolescentes en entornos de riesgo (Fagan & Tyler, 2005). A pesar de su gran relevancia e importante repercusión social, estos temas no han sido estudiados en el contexto escolar durante la adolescencia.

Dada la literatura previa y su relevancia, el presente estudio pretende aportar al conocimiento acerca de la percepción de los/las estudiantes de secundaria respecto a la JP y JD, siendo una de las primeras investigaciones llevadas a cabo en México. Asimismo, pretende generar instrumentos válidos y confiables para el estudio de estos constructos, los cuales son esenciales para la promoción de una adecuada convivencia escolar (Secretaría de Educación Pública, 2018). Finalmente, se busca explorar la relación entre la percepción de justicia en los estudiantes y la SV autoinformada.

2. Objetivos

El objetivo principal del estudio fue investigar la relación entre la satisfacción con la vida y la justicia procedimental y distributiva en adolescentes en el contexto escolar. Se derivan dos objetivos: (1) Explorar las propiedades psicométricas de las escalas MLSS-A, JP y JD en una muestra de estudiantes de secundaria de una ciudad del noroeste de México, y (2) Investigar la relación entre la percepción de la JP, JD y la SV en adolescentes en un contexto escolar. Las relaciones hipotéticas se presentan en la Figura 1.

Figura 1

Modelo teórico entre justicia procedimental, justicia distributiva y satisfacción con la vida

3. Método

3.1 Participantes

La muestra estuvo conformada por 208 estudiantes de dos escuelas secundarias (de los tres niveles) de una ciudad del noroeste de México, donde 98 reportaron ser hombres (47,1%) y 110 mujeres (52,9%). Los/las participantes tenían entre 12 y 16 años (Medad = 13,5; SD =0,92). Del total de la muestra, el 64,4% (134 estudiantes) asistía a una escuela pública, y el 35,6% restante (74 adolescentes) estudiaba en una escuela privada. En cuanto a su nivel de escolaridad, el 31,7% (66 estudiantes) estaban en el primer año, el 46,2% en el segundo (96) y el 22,1% en el tercero (46).

3.2 Diseño

Esta investigación es correlacional porque describe la relación entre las variables propuestas (Hernández-Sampieri & Mendoza, 2023). Se considera prospectiva y transversal, ya que la información fue recolectada expresamente para el estudio, midiendo las variables de interés en una sola ocasión (Hernández-Sampieri & Mendoza, 2023).

3.3 Instrumentos

3.3.1 Escala de Justicia Procedimental

La Escala de Justicia Procedimental (Procedural Justice Scale - PJS; véase el Apéndice A) es un instrumento adaptado de la Escala de Justicia Procedimental de Frías-Armenta et al. (2016) que mostró evidencias de validez de constructo y fiabilidad (α = 0,86). Consta de 21 ítems tipo Likert (por ejemplo, Cuando no estás de acuerdo con tus calificaciones y solicitas una revisión, ¿Qué tan justo crees que es el proceso de aclaración de calificaciones por parte de los profesores?) con una escala de 10 puntos ( desde 0= nada, injusto, nunca hasta 10 = todo, justo, siempre). El instrumento integra los criterios de la International Association of Judges of Youth and Family (AIMJF, 2017). Además, los criterios de Jackson et al. (2015), Meijer (2009) y Tyler (2006) deben estar presentes para que un proceso se considere justo. Incluye 6 ítems sobre consistencia, 7 sobre imparcialidad, 4 sobre transparencia y representación y 4 sobre la voz del estudiante. El instrumento evaluó la percepción de justicia experimentada durante su ingreso y permanencia en la escuela secundaria. Se hizo especial hincapié en el proceso de admisión, el proceso de evaluación de las clases y cómo se aplica la normativa escolar.

3.3.2 Escala de Justicia Distributiva

La Escala de Justicia Distributiva (Distributive Justice Scale - DJS; véase el Apéndice B) consta de 18 ítems tipo Likert (p. ej., creo que pedir aclaraciones sobre cómo me han calificado me ha ayudado, ya que obtengo una calificación justa) que utilizan una escala de 10 puntos (desde 0 = completamente en desacuerdo, en absoluto; nunca a 10 = completamente de acuerdo, todo, siempre). Basada en los principios de Bolívar (2012) y Henríquez (2018) se considera que la DJS es indispensable en el estudio de la JD. Los ítems evaluaron equidad/igualdad (6 ítems), reparación de daños (4), suficiencia (4) y priorización (4). El instrumento evaluó la percepción de la distribución justa de los beneficios recibidos durante su ingreso y permanencia en la escuela secundaria asociados al proceso de admisión, la evaluación de las clases y la aplicación del reglamento escolar en el día a día y al recibir sanciones. Frías-Armenta et al. (2016) mostraron evidencias de validez de constructo y fiabilidad (α = 0,93).

3.3.3 Escala Multidimensional de Satisfacción con la Vida de los/las Estudiantes

La Escala Multidimensional de Satisfacción con la Vida de los/las Estudiantes (Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale - MSLSS-A; Gilligan & Huebner, 2007) es un instrumento traducido al español y validado por San Martín (2011; ver Apéndice C). La MSLSS-A cuenta con 40 ítems tipo Likert de 5 puntos (de 1 = muy en desacuerdo a 5 = muy de acuerdo) que evalúan la SV de adolescentes en función de sus respuestas en 5 dominios o áreas: familia (7 ítems), amigos (9), escuela (8), entorno de vida (9) y autosatisfacción (7). San Martín (2011) reportó niveles adecuados de consistencia interna para la escala en una muestra chilena (α = 0,89 para el instrumento completo y entre 0,79 y 0,90 para los dominios). Aunque la escala puede tener algunas limitaciones, ofrece una perspectiva ecológica, incluyendo características de importancia central para los/las adolescentes (Losada-Puente et al., 2020). La escala ha sido previamente adaptada al árabe y mostró validez y fiabilidad (Veronese & Pepe, 2020). También fue validada en España y Chile, mostrando aceptable consistencia interna y fiabilidad (α = 0,86 en España) y (α = 0,88 en Chile) y validez de constructo.

3.3.4 Cuestionario sociodemográfico

Las variables sociodemográficas eran 12 ítems abiertos diseñados para recoger información sobre las características del estudiante, como la edad, el sexo, la escolarización pública o privada, el nivel educativo de los padres y si el estudiante tenía un empleo remunerado. Además, se solicitó información acerca de los ingresos familiares mensuales, en la que se pidió al estudiante que se autodeclarase utilizando 6 rangos de los cuales debía seleccionar el que creyera apropiado para su situación familiar.

3.4 Procedimiento y consideraciones éticas

En primer lugar, se informó a los directores de los establecimientos educativos del objetivo del proyecto y de lo que se solicitaría a los estudiantes si decidían participar. Se les presentaron los instrumentos para que pudieran revisar el contenido. Se solicitó la autorización de los padres o tutores tras explicarles los procedimientos y objetivos de la investigación. Se entregaron a los/las estudiantes formularios de consentimiento informado para que los leyeran y firmaran sus padres o tutores.

Se explicó a los/las estudiantes en qué consistía el estudio y su papel si decidían participar. Se les informó de las condiciones de su colaboración (anónima, voluntaria y sin efecto sobre la calificación). Un día después de haber enviado los formularios de consentimiento a los padres fueron devueltos por los/las estudiantes. Solo los/las estudiantes cuyos padres dieron su consentimiento para participar recibieron un formulario de asentimiento informado para ser parte del estudio de acuerdo con las normas éticas para el trabajo de investigación en Psicología (Sociedad Mexicana de Psicología, 2009). Luego de la firma del asentimiento se entregaron los instrumentos previamente descritos en formato de lápiz y papel, tardando aproximadamente 30 minutos en completarlos.

3.5 Estrategia analítica

En la primera fase, se analizaron las variables continuas y categóricas del estudio, se calcularon las medias y las desviaciones estándar, así como las frecuencias, utilizando el paquete estadístico IBM SPSS Statistics 23 (Field, 2020). Posteriormente, se determinó la normalidad de los datos a partir de los indicadores de Kolmogorov-Smirnov y Shapiro-Wilk. También se calcularon los coeficientes alfa de Cronbach (α) y omega de McDonald (ω) de cada escala para estimar su consistencia interna. Se calculó una puntuación media para cada subescala (4 para la PJS, 4 para la DJS y 5 para la MSLSS-A) (Malkewitz et al., 2023). Por último, se estimó el coeficiente de correlación rho de Spearman para determinar si las relaciones entre las escalas de cada constructo eran significativas.

En la segunda fase del análisis de los datos, se realizaron diversos análisis con el programa estadístico EQS v6 (Bentler, 2006). Se utilizó el método de estimación de máxima verosimilitud robusta, ya que los datos no presentaban una distribución normal (estadístico de Mardia = 52,73; p < ,05). Se realizaron análisis factoriales confirmatorios para demostrar la validez convergente de los ítems de las subescalas de JD y JP. Posteriormente, se calculó la varianza media extraída (AVE) de cada factor. La AVE es la media del cuadrado de los coeficientes lambda, y su valor debe ser superior a 0,50 para considerarse aceptable. A continuación, se evaluó un modelo de covarianza para estimar la validez discriminante utilizando JP, JD y SV como factores correlacionados. La raíz cuadrada de los valores AVE debe ser mayor que las covarianzas entre los factores para demostrar la validez discriminante (Hair et al., 2021).

Finalmente, se probó un modelo de ecuaciones estructurales para evaluar los efectos directos e indirectos de JP y JD sobre la SV (Sürücü & Maslakçı, 2020; Urbina, 2014). Para medir la relevancia de ambos modelos (covarianza y modelos estructurales), se consideraron sus indicadores de bondad de ajuste; estos indican si los datos apoyaron las relaciones especificadas en el modelo hipotético. Considerando que la significancia del indicador estadístico chi-cuadrado (χ2) es sensible al tamaño de la muestra, se estimó el χ2 relativo (χ2/gl), esperando un valor inferior a 5 (Urbina, 2014). Los indicadores prácticos estimados fueron el índice de ajuste normado de Bentler-Bonett (BBNFI), el índice de ajuste no normado de Bentler-Bonett (BBNNFI) y el índice de ajuste comparativo (CFI), que deberían arrojar un valor superior a 0,90 (Hair et al., 2021). Para medir el error de aproximación razonable relativo a la bondad del ajuste, se utilizó el error cuadrático medio de aproximación (RMSEA), que requiere un valor < ,08 (Collier, 2020). Además, se realizó un modelo de mediación utilizando la macro PROCESS para SPSS, donde la variable independiente fue la JP, la variable dependiente fue la SV, y la variable mediadora fue la JD.

4. Resultados

4.1 Consistencia interna

El alfa de Cronbach y el omega de McDonald (ω) de todas las escalas y subescalas mostraron la consistencia interna entre los indicadores de cada constructo. La Tabla 1 muestra la consistencia interna de cada una de las escalas.

4.2 Validez convergente

Los análisis factoriales confirmatorios mostraron evidencias de una aceptable bondad de ajuste estadística y práctica, lo que sugiere que las propuestas teóricas se ajustaron bien a los datos (véase la Tabla 2). Cabe mencionar que tres ítems fueron eliminados en la escala MSLSS-A (uno para el dominio escolar y dos para el dominio del entorno de vida) porque disminuían la correlación inter-ítem. Asimismo, los valores de AVE también fueron aceptables (AVEJP = ,55; AVEJD = ,65), lo que respalda la validez convergente de los ítems.

Tabla 1

Consistencia interna de las escalas y subescalas

|

Escalas y subescalas |

α |

ω |

|

Justicia Procedimental |

,90 |

,90 |

|

La voz del estudiante |

,78 |

,80 |

|

Imparcialidad |

,77 |

,78 |

|

Consistencia |

,67 |

,68 |

|

Transparencia y representación |

,69 |

,70 |

|

Justicia Distributiva |

,92 |

,92 |

|

Equidad/Igualdad |

,82 |

,83 |

|

Suficiencia |

,81 |

,81 |

|

Priorización |

,75 |

,76 |

|

Reparación de daños |

,71 |

,71 |

|

Satisfacción con la Vida |

,90 |

,90 |

|

Familia |

,85 |

,84 |

|

Amigos |

,78 |

,78 |

|

Escuela |

,79 |

,79 |

|

Entorno |

,78 |

,78 |

|

Self |

,85 |

,85 |

Nota. α = alfa de Cronbach; ω = omega de McDonald

4.3 Validez discriminante

Para calcular la validez discriminante entre la JP y la SV, y la JD y la SV, se utilizó un modelo de covarianza con los tres constructos. Correlaciones significativas se encontraron entre JP y JD (ϕ = ,89, p < ,o5), JP y SV (ϕ = ,44, p < ,05), y JD y SV (ϕ = ,51, p < ,05). Los índices de bondad de ajuste estadísticos y prácticos mostraron que el modelo teórico se ajusta bien a los datos, χ2(62) = 89,29, p = ,013; χ2/gl =1,44; BBNFI = 0,924; BBNNFI = 0,969; CFI = 0,975, y RMSEA = 0,046. Las covarianzas entre SV y JP, y SV y JD fueron menores que las relaciones entre los constructos y sus indicadores. La raíz cuadrada del AVE en JP (0,74) y en JD (0,81) fueron superiores a la correlación bivariada de cada subescala con SV, mostrando una adecuada validez discriminante de los dos tipos de justicia en comparación con la SV.

Tabla 2

Índices de bondad de ajuste de los análisis factoriales confirmatorios

|

Prueba χ2 de ajuste del modelo |

||||||||

|

Constructos |

χ2 |

gl |

p |

χ2/gl |

BBNFI |

BBNNFI |

CFI |

RMSEA |

|

La voz del estudiante |

0,10 |

1 |

0,74 |

0,10 |

1,00 |

1,02 |

1,00 |

0,00 |

|

Imparcialidad |

24,56 |

13 |

0,02 |

1,88 |

0,90 |

0,92 |

0,95 |

0,06 |

|

Consistencia |

12,94 |

9 |

0,16 |

1,43 |

0,92 |

0,95 |

0,97 |

0,04 |

|

Transparencia y representación |

1,29 |

2 |

0,52 |

0,64 |

0,98 |

1,02 |

1,00 |

0,00 |

|

Suficiencia |

0,98 |

2 |

0,61 |

0,49 |

0,99 |

0,01 |

1,00 |

0,00 |

|

Priorización |

0,42 |

2 |

0,80 |

0,21 |

0,99 |

1,04 |

1,00 |

0,00 |

|

Reparación de daños |

2,07 |

2 |

0,35 |

1,03 |

0,98 |

0,99 |

0,99 |

0,01 |

|

Equidad/Igualdad |

17,82 |

9 |

0,03 |

1,98 |

0,93 |

0,94 |

0,96 |

0,06 |